President Trump says he is pro-agriculture, so why would the Department of Agriculture announce that it plans to vacate the nation’s largest agricultural research center?[1] Some actions taken by the Trump administration have already disrupted agricultural research, so the Trump administration should be eager to avoid more bad press.[2] Furthermore, funding for agricultural research in our country has declined for decades, so right now, the nation could use investment in research infrastructure and workforce. More on this below.

For these reasons, it is odd that the Agriculture Department announced in July 2025 that it would vacate the largest agricultural research center in the country.[3] As of now, the department has not withdrawn this plan. If it ever carried it out, the department would certainly disrupt research. The facility in question is the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, which everyone calls BARC.

Trump strategists have said for years that they want to prevent bureaucrats from wielding unchecked power. This is another reason why the Agriculture Department’s actions paint the Trump administration in a bad light. In its plan to vacate BARC, the USDA (the U. S. Department of Agriculture) has tried to tiptoe around Congress, ignore stakeholders, and skip cost-benefit analysis.

What happens to BARC matters because it is big. Its offices, labs, and fields cover ten square miles in Prince George’s County, Maryland. The USDA employs over a thousand people in Beltsville although the exact number is unclear. The scope of the work done here is vast, as the following diagram shows.[4]

In the months since the July 24 announcement of its reorganization plan, the Department of Agriculture has not started to vacate BARC, as far as we know.[5] Then again, carrying out the plan would be premature because interested parties have not yet had a chance to testify before Congress on this subject. Media reports suggest there is opposition to the plan.[6] In interviews, the Secretary of Agriculture has described the reorganization as if it would only move headquarters staff out of Washington DC. She avoids mentioning that the plan would also vacate a research facility in Prince George’s County.[7]

On November 12, 2025, Congress passed a law that constrains the USDA’s ability to carry out reorganizations. The law forbids the department from relocating any office or employee without first obtaining the approval of the budget committees in the House and Senate. In addition, this law provides $3 million to continue “construction and facilities improvement” at BARC in 2026, which suggests that Congress would disapprove if the USDA were to suddenly vacate BARC.[8]

The November 12 law gives the USDA until January 11 to tell Congress how much of its 2026 budget it will spend on each of its research units.[9] Now would be a good time for members of the public to encourage the USDA to fully fund BARC. The last section of this blog post suggests some ways to make this point.

Vacating BARC would accelerate a decades-long decline in agricultural research

Agricultural research has declined on a national scale

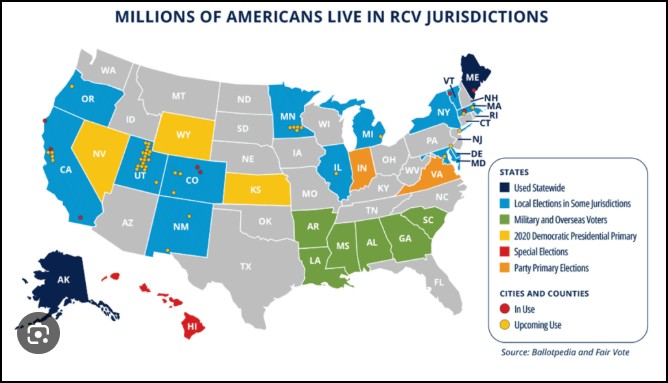

America’s status as the world leader in agricultural research slowly slipped away while China steadily increased its spending in this area. China now spends more annually on agricultural research than the United States does, as shown below in Table 1. The Chinese government has employed more agricultural researchers than the United States government since 1980, and the gap continues to widen.[10]

| Year | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | 2022 |

| Funding (corrected for inflation) | |||||||||

| USA | $1.5B | $2.7B | $3.4B | $4.3B | $5.2B | $6.3B | $5.8B | $5.0B | $5.1B |

| China | $0.086B | $0.10B | $0.20B | $0.49B | $0.83B | $1.7B | $4.0B | $7.6B | $7.9B |

| Number of full-time-equivalent (FTE) positions | |||||||||

| USA | 9,605 | 10,421 | 11,202 | 11,377 | 10,294 | 11,283 | 8,842 | 8,274 | 8,282 |

| China | 2,971 | 4,477 | 12,754 | 25,781 | 37,362 | 25,848 | 34,342 | 44,525 | 46,156 |

One can give context to the decline in the United States’ agricultural research using the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or its population. Between 2005 and 2022, funding for agricultural research decreased 19% while the GDP increased by 34% after correcting both for inflation.[12] During the same period, the number of people the federal government employed in agricultural research decreased 27% while the United States’ population increased by 13%.[13]

The USDA’s actions this year have accelerated the decline in agricultural research. Table 1 shows it took almost twenty years for the gradual decline to reach a 19% reduction in funding and a 27% workforce reduction.

During 2025, the USDA cut a similar percentage of employees and inspired Congress to cut a similar percentage of research funding. In February through April 2025, the USDA accepted the resignations of 20% of the employees of the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), which is one of four research agencies within the USDA.[14] ARS is the agency that oversees research at BARC. In May, the USDA proposed a 29% cut to research funding.[15] This proposal likely contributed to Congress deciding in November to cut USDA’s research funding by 25%.[16]

The country has been investing a shrinking percentage of its economic resources in the federal government’s agricultural research. Yet, several studies suggest that federal spending on agricultural research should be increased by about 50% above the 2024 level if the United States is to remain competitive.[17]

The nation’s largest agriculture research facility has shrunk too

A gradual and decades-long shrinking of funds for the country’s flagship agricultural research center mirrors the broader decline in funds for agriculture research, nation wide. Table 2 shows that BARC funding dropped 24% during 2006–2024 and its workforce has shrunk by more than 75% since the 1960s.

| Year | 1950s | 1960 | 1962 | 1975 | 1998 | 2006 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2024 | proposed 2026 |

| Employees | 2,399 | 2,750 | 4,800 | 1,642 | 1,291 | 1,118 | 943 | 743 | 553 | 593 | 475 |

| Inflation corrected 2025 dollars (millions) | — | — | — | $228M | $241M | $240M | $213M | $192M | 184M | 184M | $151M |

The rightmost column in Table 2 reflects the USDA’s proposal in May 2025 to cut both BARC funding and manpower. An even steeper loss would occur if the USDA did vacate BARC, an action that could cause 75% of BARC employees to resign rather than accept relocation to another part of the country. As members of Congress have pointed out, a loss this severe occurred in 2019 when the USDA moved a statistical-research agency and economic-research agency.[19]

The panoramic view in front of BARC Building 307. The pictured buildings have recently been renovated and house multiple research laboratories. To see other parts of the image, hover over it and click the left or right arrows.

In proposing that BARC be vacated, the USDA undermines a stated goal of the Trump administration

Donald Trump wrote in 2024, “American agriculture is built on science, technology and innovation and we must stay ahead of China with our science investments.” [20] Furthermore, several pro-Trump think tanks have published policy documents that are pro-science with regard to the USDA, as outlined below.

The plan to vacate BARC suggests that the USDA isn’t serious about achieving this goal. Closing BARC would lead to a lost of expertise, slow the pace of discovery, and perhaps even divert funds from research to cover the expenses associated with the relocation.[21]

The Heritage Foundation endorses science at the USDA

In April 2023, the Heritage Foundation published a 920-page blueprint for the second Trump administration. The document is called Project 2025: The Mandate for Leadership, and it proposed that the USDA’s mission statement be rewritten to focus on disseminating agricultural information and conducting research. The Heritage Foundation proposes the following as the new mission statement:

To develop and disseminate agricultural information and research, identify and address concrete public health and safety threats directly connected to food and agriculture, and remove both unjustified foreign trade barriers for U. S. goods and domestic government barriers that undermine access to safe and affordable food absent a compelling need—all based on the importance of sound science, personal freedom, private property, the rule of law, and service to all Americans. (page 291)

In emphasizing the role of science, the Heritage Foundation is loosely paragraphing the 1862 law that created the USDA.[22] Currently, only about 2% of USDA’s budget is spent on research.[23]

The America First Policy Institute endorses science and innovation at the USDA

The America First Policy Institute was founded in 2021 by Brooke Rollins, the current Secretary of Agriculture. In April 2025, the Institute published a 16-page Farmer First Agenda.[24] In this agenda, two goals in the “reorient government” section are:

- Encourage innovation in farming. This includes precision agriculture and practices that improve productivity, sustainability, and the nutritional integrity of American made foods.

- Ensure food safety regulations and policies implementing food safety laws are based on the best available science.

Nowhere does the America First Policy Institute talk about disrupting or reducing agricultural research.

The Center for Renewing America endorses science at the USDA

In 2021, Russell Vought founded the Center for Renewing America, and he is currently the director of the Office of Management and Budget. In 2022, the Center for Renewing America recommended reducing government spending in many areas,[25] but agricultural research was not one of them. The Center proposed an 11% cut to the USDA’s budget but no cut to the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service.[26] In this way, the Center for Renewing America expressed a desire to increase the fraction of the USDA budget spent on research.

Republicans have historically invested in agricultural research facilities

Were the USDA to abruptly vacate a major agricultural-research facility, then it would appear disloyal to traditional Republican priorities. Under the two administrations of George H. W. Bush, there was a significant increase in funds to build or renovate facilities for the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS). Annual investment increased from $102 to $191 million, comparing 2001 to 2007. Budget cuts subsequently occurred. Then, under the first Trump administration, funding increased again to build or renovate ARS facilities, this time from $6 to $100 million annually, comparing 2017 to 2021.[27]

In some ways, the Republican-controlled Congress in 2025 has signaled support for agricultural research. Congress passed the Big Beautiful Bill in July 2025 that contained $1.6 billion in new funds for agricultural research. These new funds are to be spent over several years. This funding increase is much larger than the sum of all other civilian-research funding in the Big Beautiful Bill.[28] It is true that Congress passed a USDA budget in November 2025 that cuts USDA research funding by 25% relative to FY 2024 funding.[29] But despite this cut, Congress can still be seen as favoring agricultural research because the Trump Administration is pushing for much steeper cuts in other types of research. (See Appendix A of the present blog post.)

The Secretary of Agriculture claims to support science

The Secretary of Agriculture says that research is important to her. In May 2025, Secretary Rollins told a Senate committee:

Obviously, the research is a key component of the work at USDA…. I believe that none of that will be compromised. Senator, if you see something different on the ground in Michigan or across the country, would you please flag it for us because it shouldn’t affect the key most important parts of the research? [30]

During this hearing, Secretary Rollins claimed that cuts to research would be small if Congress were to pass the president’s proposed 2026 budget. She said:

The research part of… the budget that came out Friday went from 2.1 billion down to 1.9 billion. So while it is a cut, it’s not a massive cut. It’s a 7% cut, and it’s very much focused on outdated facilities.[31]

At this hearing, Secretary Rollin failed to mention relevant facts. The FY 2026 proposed cut to USDA research funding is much deeper than Rollins’ 7% figure if you use FY 2024 as a baseline. Congress never passed a budget for the USDA for FY 2025. The annual funding for USDA research would drop from $5.0 to $3.6 billion, which is a 29% cut, if you compare the FY 2024 budget that Congress enacted to the president’s proposed budget for FY 2026.[32]

In the above quote, Secretary Rollins’ comment about outdated facilities does not make sense. She suggested that the proposed cuts to research were no big deal because they were due to some facilities being outdated. For one thing, the proposed FY 2026 budget significantly cuts BARC funding, yet many BARC buildings have been updated recently. The federal government has invested over $460 million on building construction and renovation at BARC since 1988. This spending is described in Appendix B of this blog post.

Furthermore, it is common sense that, when a facility is outdated, there is a need for additional funds, not a funding cut. Specifically, funds are needed to fix or replace that facility. To reinforce this point, consider the one place where the word “outdated” is used in the 57-page FY 2026 budget justification for the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. On page 20-16 of this document, the USDA asks Congress for $6 million of additional funding as part of an effort to replace an outdated agricultural-research facility in New York.

Seduced by deconstruction

As described above, organizations developing policy for the Trump administration have stated the goal of protecting or even reinvigorating agricultural research. Has the USDA been distracted from this worthy goal, seduced by a desire to deconstruct? In a Fox News interview, Secretary Rollins said that the July 24 USDA reorganization plan was great because it would contribute to deconstructing the administrative state.[33] At a conference in September, the director of the Office of Management and Budget suggested that deconstruction means starving an agency of funds, reducing its ability to function, or having Congress legislate it out of existence.[34]

The panoramic view in front of BARC Building 003 in October 2025. The buildings pictured have recently been renovated or are currently being renovated. They house multiple research laboratories. To see other parts of the image, hover over it and click the left or right arrows.

The way the USDA has handled its plan to vacate BARC mocks the Trump administration’s goal of reigning in unelected bureaucrats

Bureaucrats failing to inject reason into their decisions

The USDA has yet to make the case that the benefits of relocating BARC outweigh the cost, as discussed in a prior post to the Greenbelt Online blog. For this reason, the Secretary’s July 24 announcement that the USDA would vacate BARC appears to be an impetuous decision made by a bureaucrat who failed to inject reason into the discussion. Using almost these words, the Heritage Foundation warned about the harm that an unelected official can cause.[35]

The Heritage Foundation also warned that an unelected official should not be allowed to use speculative benefits to justify his or her actions.[36] In its written communication, the USDA has not even bothered to speculate quantitatively about any potential benefit to vacating BARC. During an interview on July 25, the Secretary of Agriculture speculated that the USDA’s headquarters staff would provide better service to the American people if their offices were located in a city other than Washington DC.[37] The secretary didn’t bother to speculate whether or not the same benefit would come from moving researchers out of BARC in Prince George’s County.

Without citing any data, Secretary Rollins guessed that only 50% of USDA employees would quit rather than relocate because President Trump had begun a golden age for the economy. In the same interview, she also said that, if her forecasted 50% loss did occur, it would earn her high marks with the president.[38] The secretary’s speculation was contradicted a few days later by Deputy Secretary Vaden. On July 30, 2025, Vaden told the Senate that President Trump had damaged the local economy, so most USDA employees facing relocation would take it rather than resign.[39]

How Trump allies recommend restraining bureaucrats

The American First Policy Institute wants to prevent agency guidance documents from taking effect without an affirmative vote from Congress.[40] Similarly, the Heritage Foundation believes that the push and pull between the Senate and House prior to legislation passing as an antidote to unelected officials getting their way by merely publishing a guidance document. One type of guidance document is a memorandum published by the head of a department in which he or she gives employees guidance on how to exercise their discretion in carrying out their Congressionally funded and authorized duties.[41]

The USDA’s July 24 memorandum is an example of an agency guidance document. The memorandum is flawed because it did not call for an affirmative vote from Congress or any role for Congress at all in the proposed USDA reorganization. Congress has not voted to authorize the actions in the USDA’s plan. The plan has received no hearing in the House and only one hearing in the Senate. This Senate hearing featured just one witness, a Trump appointee. Two senators gave that appointee, USDA Deputy Secretary Vaden, the opportunity to affirm that Congress would need to vote to authorize and fund the USDA reorganization before this reorganization could proceed. Vaden declined to affirm that statement.[42] Congress has since rejected the USDA’s attempt to avoid Congressional oversight. On November 12, 2025, Congress passed a law that requires two committees in Congress to approve before the USDA can carry out any sort of reorganization.[43]

A second way that the American First Policy Institute recommends limiting the harm that bureaucrats can cause is to never let them get away with authoritatively interpreting the law.[44] But the USDA’s July 24 memorandum attempts to do exactly this dangerous thing. The July 24 memorandum lists a 1953 law as justification for vacating BARC, but a straightforward reading of the law suggests that it provides no legal cover for such an action. So far, no court has ruled on the USDA’s interpretation.

The 1953 law directs the USDA to “place the administration of farm programs close to the state and local levels.” [45] According to the Congressional Research Service, the term “farm program” refers to a financial assistance program for individual farms, not to the USDA’s research programs or other activities.[46] The USDA offices that administer farm assistance already operate at the local level, with 2,300 offices across the country.[47] In contrast, the work performed at BARC is agricultural research. It is widely recognized that research is more productive when it’s done in a location with a critical mass of researchers. At such a location, collaboration is more likely, which can accelerate the pace of discovery.

A third way that conservatives believe bureaucrats can be brought to heel is for ordinary citizens to education themselves on the issues and speak out.[48] The other half of this solution is for bureaucrats to listen and to allow themselves to be influenced by well-founded opinions. The Agriculture Secretary understands the importance of meeting people in person to listen to their concerns. For example, she traveled to Tennessee in September 2025 for a listening session at an event organized by the Tennessee Farm Bureau Federation.[49] On the other hand, she has not held an in-person listening session with local residents and interested organizations about her proposal to vacate BARC. It’s an issue definitely big enough to warrant her personal attention. As mentioned at the beginning of this blog post, BARC employs over a thousand people on a campus that covers 10 square miles of Maryland farmland and forest. Secretary Rollins’ decision-making process with regard to BARC appears remote and unanswerable, to use a phrase from an article she wrote in 2023.

Alternatives to vacating BARC

To summarize, strategists for the Trump administration advertised that the new administration would maintain or boost agricultural research, as described earlier in this blog post. Yet, the Department of Agriculture took three actions in 2025 that moved the country in the opposite direction. During February to April, the USDA accepted the resignations of 20% of its research staff. In May, the USDA proposed a 29% cut to research funding. In July, the USDA announced a reorganization plan that includes vacating the country’s largest agricultural research center, which is the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center (BARC).

If the USDA’s leadership were serious about championing agricultural research, then there are alternatives that the department should consider. The following diagram contrasts the USDA’s proposed action (vacating BARC) with other alternatives.

Investing in our country’s flagship agricultural research facility is one way to start to reverse the decades of decline that have occurred on a national scale. If appropriately funded, BARC could lead the charge because it has carried out an orderly retreat rather than a rout during recent decades. Despite decreased funding and staffing, BARC’s scientific output has remained strong.[50] Essential facilities are in good repair because BARC carefully chose how to spend available funds for building construction and renovation. Since 1988, over $460 million has been spent on construction and building renovation at BARC.[51] BARC’s recently renovated office buildings have space for more employees.[52]

As discussed in a prior blog post, the area surrounding BARC has a critical mass of USDA researchers and nearby researchers in related fields. The map below shows where some of these facilities are. The opportunities for collaboration are great when there are tens of thousands of workers at research and agriculture-related organizations nearby. Within 10 miles of BARC, the following organizations have facilities: NASA, NOAA, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the USDA inspection service, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the University of Maryland.[53]

Appendix A: Proposed cuts to funding for federal research

The table below states the cuts to federal research that the Trump administration proposed in May 2025 for Congress to consider passing for fiscal year (FY) 2026. The table compares the proposed FY 2026 spending levels to actual spending during FY 2024. While Congress passed an FY 2026 budget for the USDA on November 12, 2025, many research organizations still lack a Congressionally approved FY 2026 budget.

| Organization | Actual in FY 2024 | Proposed for FY 2026 | Percent change | Notes |

| NOAA OAR | $0.782B | 0 | -100% | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) a |

| CDC | $9.683B | $4.321B | -55% | Center for Disease Control and Prevention b |

| NSF | $9.23B | $4.144B | -55% | National Science Foundation c |

| EPA | $9.100B | $4.200B | -54% | Environmental Protection Agency d |

| NASA SMD | $7.325B | $3.908B | -47% | Science Mission Directorate at NASA e |

| NIST | $1.460B | $0.832B | -43% | National Institute of Standards and Technology f |

| NIH | $46.358B | $27.915B | -40% | National Institutes of Health g |

| USGS | $1.455B | $0.891B | -39% | U. S. Geological Survey h |

| USDA | $4.99B | $3.56B | -29% | The four research agencies within the U. S. Department of Agriculture are ARS, NISS, NIFA, and ERS i |

a NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) was zeroed out in the president’s 2025 proposal for NOAA’s FY 2026 budget. The OAR funding in FY 2024 was stated on page 30 of the 82-page FY 2024 NOAA Blue Book. That the OAR is zeroed out in the FY 2026 proposal is stated on page 181 of NOAA’s 396-page FY 2026 budget justification (page OAR-1). The proposal for FY 2026 transfers a few projects out of OAR, but most OAR projects would be terminated including the Hurricane Research Division.

b The CDC’s budget during FY 2024 was merely a continuing resolution that kept funding at the FY 2023 level passed by Congress. The CDC’s FY 2025 budget justification document states that the CDC’s FY 2024 budget was $9.683B. Contradicting these numbers, the CDC’s FY 2026 budget justification document states different values for FY 2024 and says they are “adjusted based on proposed HSS reorganization.” The CDC’s FY 2026 budget justification also states $4.321B as the CDC proposed FY 2026 budget.

c The summary table on page 19 of the 222-page May 2025 NSF budget justification for the president’s proposed FY 2026 budget.

d Page 17 of the EPA budget in brief for the president’s proposed FY 2026 budget.

e The actual FY 2024 and proposed FY 2026 budget for the NASA Science Mission Directorate (SMD) is stated on page BUD-3 of the technical supplement to NASA’s 2025 budget justification for the proposed FY 2026 budget.

f On June 11, 2025, the NIST acting director of program coordination published a 13-page slide presentation providing a “NIST Budget Update.” On page 11 of this presentation, NIST’s actual FY 2024 and proposed FY 2026 budget is stated.

g The NIH “total program level” of funding is stated on page 23 (page 29 of the 120-page PDF file) of the NIH congressional justification for its proposed FY 2026 budget.

h FY 2024 and FY 2026 values are stated in the USGS Bureau Highlights document in a table titled “Highlights of Budget Changes” on page USGS-4.

i For the details on this USDA data see the earlier footnotes on the president’s proposed 29% USDA budget cut and the 25% budget cut that Congress approved on November 12, 2025.

On May 5, 2025, the American Geophysical Union published a similar list of proposed research cuts to those stated in the table above. These cuts are mere proposals, but the president’s proposed budget has more significance this year than it normally does. As evidence that the FY 2026 budget proposal is being handled differently than normal, consider that NASA is alleged to have cut research spending in June 2025 to align it with the president’s proposed FY 2026 budget even though Congress never passed that budget proposal. A Senate report asserts that such an action is illegal because a president’s budget proposal does not carry the force of law, while a budget passed by Congress does. See also the NASA-related November 6, 2025, front page story in the Greenbelt News Review.

Appendix B: BARC building and renovation, 1988–2025

The following table shows a total of $465 million spent by the USDA on building construction and renovation at BARC since 1988. This total might not include the cost to build or renovate BARC buildings that house organizations other than ARS, such as the APHIS Plant Pathogen Diagnostics Laboratory in BARC building 580, the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) Berg National Plan Materials Center in BARC building 509, or the University of Maryland’s Central Maryland Research and Education Center on the BARC East Farm. This table does not include the $3 million for BARC construction and renovation given in the FY 2026 USDA budget that Congress passed in November 2025.[54]

| Building category | 1988–2006 | 2009–2010 | 2016–2025 |

| ARS BARC including the Beltsville HNRC a | $151.789M b | $14.208M c | 163.4M d |

| ARS National Agricultural Library | $9.651M b | $6.242M c | zero |

| USDA George Washington Carver Center (GWCC) | $37.7M e | zero | $82.4M f |

a Constructed during 2000–2001, the Human Nutrition Research Center (HNRC) in Beltsville is a research center that currently has 5 research groups (4 labs plus the Human Research Facility). The center is located on the BARC campus. These research groups are different organizations from the 17 laboratories listed by ARS as being BARC laboratories.

b During 1988 to 2006, the $152M for BARC generally and the additional $10M for the library are stated on page 10-69 of the USDA budget justification published in 2008 for FY 2009. See the archive of USA budget justification documents. These dollar figures are not corrected for inflation. They do not include the cost of periodically replacing scientific equipment in the laboratories.

c In 2009 and 2010, $14.208M was spent on BARC generally ($21.039M +$3.000M -$9.831M) and an additional $6.242M was spent on the library ($6.357M – $0.115M), according to page 16-80 of the 2012 justification of the USDA’s proposed FY 2013 budget.

d The USDA’s 2024 justification for the proposed FY 2025 budget states the following was spent on BARC buildings during 2016 to 2024: $35.5M, $12.3M, $26.5M, $46.1M, $0.5M, and $5.4M. The USDA’s 2025 justification for the proposed FY 2026 budget repeats some of these figures and also states the following additional spending: $16.0M, $10.0M, and $12.45M. Summing all these values results in a total of $163.4M.

e In September 1998, Gordon Wright wrote that it cost $33.7 million to construct the GWCC: Building Design and Construction, volume 39, issue 9, which is archived in Gale eBooks.

f The cost of renovating the GWCC in 2020–2022 is stated as $82.4 million on the Grunely Construction company’s website, the firm that did the work. In 2020, the original award for the renovation was $75.37 million according to the General Services Administration.

[1] During the 2024 campaign, Donald Trump wrote, “I am proud to be the most pro-farmer president ever” and he added that “American agriculture is built on science, technology and innovation and we must stay ahead of China with our science investments.” This quote is taken from a questionnaire that Donald Trump filled out for the American Farm Bureau Federation. The Federation posted it on its website. Quotes from this text were used in an article on the Fresh Fruit Portal news website on November 7, 2024.

[2] Ayurella Horn-Muller, March 25, 2025, Farmers are reeling from Trump’s attacks on agricultural research, Grist.

[3] The USDA’s reorganization plan includes vacating BARC, including BARC’s George Washington Carver Center (GWCC). On July 24, 2025, the USDA reorganization plan was described in a 5-page memorandum from Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins. The same day, she released a 5-minute video address to USDA employees that summarized the plan. BARC is the largest agricultural research facility in the United States: Appendix A of Kelley’s September 16, 2025, post to the Greenbelt Online blog.

[4] The pie chart shows that ARS had 520 and 73 full-time-equivalent (FTE) non-headquarters employees working at BARC and at the National Agricultural Library, respectfully. These employee counts are for fiscal year (FY) 2024 and are stated in the geographic-breakdown section of the FY 2026 ARS budget justification that was published in May 2025. The pie chart shows a lower estimate of 597 FTE for the George Washington Carver Center (GWCC) on the BARC Link Farm. This value for 2024 comes from counting 499 ARS headquarters staff at GWCC plus the additional personnel listed during the fall of 2025 in the USDS online directory: 39 USDA CIO employees, 32 USDA NRCS employees, and 27 USDA FPCBC employees. To query the online directory, a county of “Prince” was selected in the State of Maryland. “Prince” is short for “Prince George’s County.” The upper estimate of 823 FTE for GWCC is taken from the 2017 USDA telephone directory for the Washington DC area. This 89-page PDF file lists 823 employees whose office location is “GWCC.”

It is a fiction perpetrated by the USDA in some of its documents that the 499 members of the ARS headquarters staff work in the District of Columbia. For example, the FY 2026 ARS budget justification does so. In contrast, their offices are actually located at GWCC in Maryland. The ARS headquarters information web page states that the headquarters staff have their offices at GWCC:

Do not trust the USDA online directory to accurately count the number of current BARC employees. In November 2025, the online directory returned only 112 employees with offices in “BELTSVILLE” when one requests the listing for employees in Maryland. The 112-employee figure seems much too low because there were 520 FTE in FY 2024 according to the ARS budget justification for FY 2026 that was published in May 2025. The 520 figure for BARC in FY 2024 excludes employees at the GWCC and National Agricultural Library.

[5] The USDA did have a public-comment period in August and September, but there is no evidence that the USDA has seriously considered these comments or revised the reorganization plan based on them. After July, the only mention the USDA has made of the plan to vacate BARC may be a few sentences during a TV interview. On August 28, 2025, a correspondent with ABC 7 News in DC asked Secretary Rollins what her message was to BARC employees. Rollins responded that vacating BARC is justified because federal workers “are here to serve the American people,” the Trump administration doesn’t want the public “beholden to some bureaucrat in Washington,” and the Trump administration wants “incredible prosperity” for the country.

[6] The only hearing on the USDA reorganization plan was a Senate hearing on July 30, 2025, with a single witness, Deputy Secretary Vaden. If agricultural trade organizations were given a chance to testify, they might argue for increasing research spending rather than disrupting it by vacating BARC. In 2019 at least, there was widespread support for increasing agricultural research spending: Senator Dick Durban (Democrat from Illinois), September 10, 2019, Durbin Introduces Bill To Boost Agricultural Research Funding, press release.

On September 26, 2025, the Maryland Farm Bureau wrote to USDA Secretary Rollins saying that it was “strongly opposed to the proposed relocation and closure of” BARC. On July 28, 2025, the Progressive Farmer website reported that the National Farmers Union was concerned that such a major reorganization could cause “significant staff turnover, loss of institutional knowledge and service disruptions, at a time when farmers, ranchers and their communities critically depend on these services to stay afloat.” In the same story, it was reported that the American Farm Bureau Federation said it was very important that “delivery of essential services and programs for farmers is not disrupted.” On September 17, 2025, the Federation of American Scientists said that the USDA reorganization and its planned facility closures threaten the country’s capacity for agricultural research. Other criticism of USDA’s cuts to research spending: Ayurella Horn-Muller writing on Grist.org on March 25, 2025. The Trump administration is harming agricultural research outside of the USDA too according to Karl Plume and P. J. Huffstutter writing for Reuters on April 17, 2025.

[7] In a July 25, 2025, interview with Fox News, Secretary Rollins said, “yesterday, USDA announced we are going to be moving most of our headquarters staff out into the country.” On August 28, 2025, Rollins said the following in an interview with ABC 7 News WJLA in Washington DC: “now we are moving most of our headquarters out of DC.” In that interview she also said, “We did make the decision to shut down, I think, 5 buildings in Washington…. Why are we holding onto these really expensive buildings that no one is using for office space when in fact we should be in office space out in the country where we can better serve the people?” BARC, incidentally, is located in fields and forest of Prince George’s County, Maryland, and has over a thousand employees.

[8] On November 12, 2025, Congress passed Public Law 119-37. Section 716 of this law limits the ability of the USDA to carry out reorganizations (page 50 of H. R. 5371). Page 19 states $3 million of funding for BARC “construction and facilities improvement.”

[9] The USDA’s budget proposal for FY 2026 contains a specific funding level and a proposed number of employees at BARC. In contrast, these details about BARC are absent from the November 12, 2025, appropriations law that Congressed passed that contains the USDA’s FY 2026 budget. Congress apparently thinks that oversight is needed if the USDA to make good choices in filling in these details. The November 12 law includes a requirement that the USDA provides these details within 60 days. The relevant passage of the law is the following: “That no later than 60 days from the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary [of Agriculture] shall provide a report to the Committees on Appropriations of both House of Congress that outlines the current funding levels, staffing levels, and hiring plans in fiscal year 2026 for each research unit” (page 18 of H. R. 5371).

[10] Speaking to the Secretary of Agriculture, Senator Gary Peters (Democrat from Michigan) said, “we’ve seen competitors such as China surge in their research efforts. They’ve now far surpassed U. S. investment in agricultural research as well as development. And given the critical importance of food security to national security, China competitiveness in this context, I think, is of such utmost importance for us to keep an eye on. That’s why I’m frustrated to see that the President’s Budget calls for hefty cuts in research funding. So my question for you, Madam Secretary, is a research a priority for this administration? And if so, how do you square that with this year’s budget request” (1:21:00, May 6, 2025, Senate Appropriations Committee hearing).

Donald Trump wrote during the 2024 campaign that “American agriculture is built on science, technology and innovation and we must stay ahead of China with our science investments.”

[11] Table 1 shows the number of positions and amount of government funding in the United States and in China as reported in the file grape_v1.0.0.xlsx. This dataset is described in Dijk, M. van, K. Fuglie, P. W. Heisey, and H. Deng, 2025, A global dataset of public agricultural R&D investment: 1960–2022, Scientific Data, doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05331-y. Dijk et al. (2025) report the 1960 to 2022 values in constant 2017 dollars, i.e., corrected for inflation. Consistent with with Dijk et al. (2025), the USDA reported in 2016 and 2022 that Chinese government spending on agricultural research exceeds that of the United States. In the United States, corporations now spend more on agricultural research than does the government. This report and similar reports are available from the USDA Economic Research Service.

[12] Based on Table 1 of the present blog post, funding (after correcting for inflation) for United States government-funded agricultural research decline during 2005 to 2022 by 19%, i.e., 100%( 1- $5.1B/$6.3B). According to the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, the U. S. Gross Domestic Product was $12.767 and $25.250 trillion in quarter 1 of 2005 and 2022, respectively, before correcting for inflation. The CPI change during this period was a factor of 1.474, so real GDP was $18.819 trillion in 2005 when expressed in 2022 dollars. Based on these values, real GDP increased by 34% between 2005 and 2022: 34% = 100%( $25.250T / $18.819T ) -100%.

[13] As shown in Table 1 of the present blog post, employment in the United States’s government-funded agricultural research declined during 2005 to 2022 by 27%, i.e., 100% (1 – 8,282/11,283 ). According to the US Census bureau, the United States population was 296 million in 2005 and 333 million in 2022, which is a 13% increase.

[14] The Investigate Midwest article “Farming the Dark” cites the Progressive Farmer website that claims 1,255 employees left the USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) during two rounds of the Deferred Resignation Program (DRP). ARS budget justification for FY 2026 states that the agency had 6,285 full-time-equivalent positions in FY 2024, so the loss of 1,255 ARS employees in early 2025 represents a 20% reduction in manpower: 100% ( 1,255/6,285 ). Among all four USDA research agencies, 1,600 employees were lost in early 2025 according to Reuters. Senator Klobuchar stated that the loss of 1,600 employees prevents the Agriculture Department from carrying out needed research. She made this statement 19:35 minutes into the July 30, 2025, Senate Agriculture Committee hearing. The same Reuters article reports that, in the entire Agriculture Department, 3,877 employees signed Deferred Resignation Program (DRP) contracts in February 2025 and 11,305 in April 2025, which is a total of 15,182 resignations through DRP. This total does not include fired civil servants, civil servants who quit without invoking the DRP, and contractors who lost their job because the USDA terminated their grant or contract.

[15] In various USDA agencies’ budget justification documents, the “total available” funding line from the May 2025 proposal for FY 2026 states both the president’s proposed funding for FY 2026 and also the actual funding during FY 2024. The USDA’s four research agencies are the Agricultural Research Services (ARS), National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), National Agricultural Statistical Service (NASS), and Economic Research Service (ERS). For these four agencies, the ratio of proposed FY 2026 funding to actual FY 2024 funding is ($1.990B + $1.308B + $0.185B + $0.080B) / ($2.222B + $2.481B + $0.199B + $0.091B) = $3.56B / $4.99B. This change would be a decrease of 29% between FY 2024 and FY 2026.

[16] The law that reopened the government after the October 1 to November 12, 2025, shutdown included the full-year FY 2026 budget for the USDA. In this law, the funding for the USDA’s four research agencies totals $3.761B, which represents at 25% cut relative to the FY 2024 funding level of $4.99B. The FY 2026 funding is as follows: $0.091B for ERS, $0.185B for NASS, $1.973B for ARS, and $1.692B for NIFA ($1.076B +$0.012B +$0.562B +$0.41B).

[17] In 2025, a Cornell University study estimated that annual USDA research funding would need to increase from about $5 billion to $6 to $8 billion for the country to remain competitive. The same year, the National Academies of Science published a paper that recommends a similar increase in agricultural research spending. In 2023, the Crop Division of the Great American Insurance Group also recommended increased spending in this area. A 2021 report by the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities stated that investment is needed in the infrastructure for agricultural research: a summary and the full report are online.

[18] The number of BARC employees and the BARC annual budget are found in the annual USDA Agricultural Research Services (ARS) justification for the president’s proposed budget for the next fiscal year. These annual documents are available for 2008 through 2026 on the Archived USDA Explanatory Notes web page. The budget justification document for some earlier years can be found elsewhere online. To create Table 2, take values from the year prior to the year that the budget justification was published. The prior-year data is the most recent data that reflects actual spending rather than estimated spending for the current year or proposed spending for the following year.

[19] In 2022, the General Accounting Office (GAO) reported on USDA agency relocations. The GAO report explored the impacts of the first Trump administration moving the Economic Research Service (ERS) and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) from Washington DC to Kansas City, Missouri, in 2019. Figures 3 and 4 of the 2022 GAO report show that, in 2021, there were 83 and 51 employees of ERS and NIFA, respectively, who had worked at their agency for more than 2 years. There were 561 employees at the two agencies in 2018 (561 = 44+229+52+236). Putting these numbers together shows that 76% percent of the people working for these two agencies in 2018 had left by 2021: 76% = 100% – 100% (83+51)/561. Rounding to 75%, Angie Craig, the ranking member of the House Committee on Agriculture, mentioned this employee loss in a press release on July 25, 2025. Senator Amy Klobuchar also mentioned a 75% loss, doing so when questioning USDA Deputy Secretary Vaden at the July 30, 2025, Senate hearing. Klobuchar provided a transcript of her questioning of Vaden.

[20] American Farm Bureau Federation website.

[21] See the General Accounting Office’s 2022 report about the 2019 relocation of ERS and NIFA.

[22] Congress created the USDA on May 15, 1862. The law was published in 12 Stat. 387 and codified in 7 U.S.C. Section 2201. The 1862 law stated that the Department of Agriculture is “to acquire and to diffuse among the people of the United States useful information on subjects connected with agriculture in the most general and comprehensive sense of that word, and to procure, propagate and distribute among the people new and valuable seeds and plants.”

[23] In FY 2024, the USDA spent $5 billion on its four research agencies out of a total budget of $238 billion. The FY 2024 data for each research agency can be found in their 2025 budget justifications for the president’s proposed FY 2026 budget. The total FY 2024 funding for the USDA is show in Figure OV-2 on page 2 of the department’s FY 2025 budget summary.

[24] This PDF file was last modified on April 25, 2025, according to the Wayback Machine.

[25] Coral Davenport, October 3, 2025: The Man Behind Trump’s Push for an All-Powerful Presidency, New York Times. ProPublica, October 17, 2025: The Shadow President, YouTube video.

[26] Center for Renewing America, December 2022, A commitment to end woke and weaponized government: 2023 budget proposal, 104 pages.

[27] Annual spending on physical plant for agricultural research is stated in the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) 2023–24 Survey of Federal Funds for Research and Development. Table 69 covers 2015–2024 and Table 68 covers 2004–2014. Table 100 of the 2021 edition of the survey covers 2001 to 2011. The Wayback Machine has values for physical plant covering 1967–2001 from another NSF document.

[28] The House Budget Committee wrote a 1,311-page report on the Big Beautiful Bill (the parent web page). This reports states, “This legislation is the principal vehicle to advance President Trump’s America First agenda.” The Big Beautiful Bill includes $1.6 billion in increased funding for agricultural research according to the Farm Bureau Market Intel website. This research funding is stated on several pages of the bill. It is difficult to determine the exact amount of funding because the funding is spread out over as many as six years. Funding is expressed in millions of dollars on page 39 of the 311-page document, which is section 10604 “Research.” This section contains the following funding: $37 +$60 +$8 +$80 +$175 +$125 +$2/year × 6 years. In section 10607, one finds additional agricultural research funding of $233/year × 5 years, $45/year forever, $2.25/year × 6 years, and $25/year × 6 years, also expressed in millions of dollars. The other civilian department that received research funding in the Big Beautiful Bill is the Department of Energy. It received just $0.15 billion, which is to be spent on building cloud-computing infrastructure for scientists (page 83 of the 331-page law).

[29] As mentioned in an earlier footnote in this blog post, Public Law 119-37 passed on November 12, 2025. This law cuts funding for the USDA’s four research agencies to $3.791B for FY 2026 from $4.99 in FY 2024, which is a 25% cut.

[30] May 6, 2025, Senate Appropriations Committee hearing on the president’s proposed budget for FY 2026 for the Agriculture Department (1:21:42).

[31] Near the same time in the May 6, 2025, Senate hearing as the prior quote.

[32] Earlier in this blog post, a footnote provides data supporting the 29% funding cut. On March 9, 2024, Congress passed a budget for the USDA for FY 2024, a fiscal year that was about half over by that time. The FY 2024 budget was passed as part of Public Law 118-42. According to a Congressional Research Service report in May 2025, Congress never passed an FY 2025 budget for the USDA and instead started debating a budget for FY 2026. During 2025, the USDA was funded merely by continuing resolutions.

[33] Background on Rollins: Ian Ward, October 10, 2025, Trump loves her. His allies don’t trust her, Politico. June 1, 2025, Q&A with Brooke Rollins: Fighting for the Soul of America, Decision Magazine.

Background on deconstruction: On February 14, 2025, President Trump’s Executive Order #14,210, required the Office Of Personnel Management to direct agencies to develop reduction in force (RIF) and reorganization plans that reduce agency activities to only those required by law. On February 25, 2025, President Trump’s Executive Order #14,219 empowered DOGE to “commence the deconstruction of the overbearing and burdensome administrative state” by getting rid of regulations.

Deconstructing the USDA: On July 25, 2025, Secretary Rollins spoke on Fox News about the USDA reorganization that had been announced the prior day and that includes vacating BARC. During that interview, Rollins said, “this is literally what he has tasked his cabinet to do: to deconstruct the administrate state in Washington DC…. yesterday, USDA announced we are going to be moving most of our headquarters staff out into the country…. Our best guess is that perhaps 50–70% of our Washington DC staff will want to move…. But those that don’t, listen, the economy is beginning to thrive again. The golden age is here. President Trump’s vision was always to move people out of these government jobs where maybe it’s not the most productive use into the private sector. We feel really good that we’ll be able to hit those marks.”

[34] On September 3, 2025, Russel Vought, the director of the Office of Management and Budget, said the following at a National Conservatism conference: “President Trump won… we have now been embarked on deconstructing this administrative state” (18:00). Vought talked about the Trump administration using impoundment, recission, and “DOGE cuts” (21:04), while also working to erase agencies that “shouldn’t exist” (21:50). Vought is member of Trump’s inner circle: Coral Davenport, October 3, 2025; and ProPublica, October 17, 2025.

[35] In an article claiming that the United States is a republic not a democracy, the Heritage Foundation asserted that our federal government is structured to “apply a brake to impetuous decisions, inject reason into impassioned debates, and help make far sighted decisions.”

[36] In an article, the Heritage Foundation warns, “Because they don’t have to answer to the voters, agency regulators are much more likely to overlook the real-world impacts and costs of their decisions on the average person, to manipulate science and distort economic reality, and to inflate the supposed benefits of their preferred outcomes—benefits that are often extremely speculative, fanciful, and untested.”

[37] Interview with Fox News on July 25, 2025.

[38] In an interview with Fox News on July 25, 2025, Secretary Rollins said: “our best guess is that perhaps 50–70% of our Washington DC staff will want to move. They will actually take that relocation. Those that don’t want to move, we will fill those positions again in North Carolina, and Indiana, in Utah, and Colorado, and Missouri. But those that don’t, listen, the economy is beginning to thrive again. The golden age is here. President Trump’s vision was always to move people out of these government jobs where maybe it’s not the most productive use into the private sector. We feel really good that we’ll be able to hit those marks.”

[39] At the July 30, 2025, Senate hearing, Deputy Secretary Vaden responded to a question from Raphael Warnock about what fraction of USDA employees would accept relocation rather than resign. Vaden responded, “I think many of them will choose to come because, given cuts made by other federal agencies here in Washington DC, the job market isn’t what it once was” (1:20:42). Deputy Secretary Vaden also stated that the USDA hopes that all relocated employees choose to stay with the department: “Employees who accept their new locations, they’ve got a job and we’ve got an office for them” (57:00) and “We have made it commitment that if employees go with us to these new locations, they’ve got a job and we are planning to have an office for them there” (1:20:17).

[40] An affirmative vote from Congress: page 14 of American First Policy Institute’s policy pillar #10 on its web page titled, “Fight government corruption by draining the swamp.”

[41] For example, a 2016 article in the Washington Law Review discussed a secretary of a federal department issuing a memorandum to the department’s underlying agencies to provide “guidelines for federal agencies to consider when exercising their prosecutorial discretion” (page 699).

[42] At the July 30, 2025, Senate hearing on the USDA reorganization plan, the two senators addressing Vaden on this point were John Hoeven (Republican from North Dakota) and Deb Fischer (Republican from Nebraska). Hoeven said: “we want it to be a process where you work with Congress, with the Senate, both the authorizing committee and the appropriations committee on it and we achieve those results together” (27:10). Fischer said: “I have to express disappointment in how this has been rolled out and the lack of engagement with Congress prior to the [July 24, 2025] announcement. And I also agree with Senator Hoeven that, to accomplish a major reorganization, Congress will need to a partner to provide resources and perhaps additional authorities” (1:14:22).

[43] On November 12, 2025, Congress passed a law that requires a general form of Congressional oversight of USDA reorganizations. Congress retains the authority to pass more specific laws in this area. The November 2025 law is Congress’ way of giving the USDA a mild rebuke for the department’s July 24, 2025, reorganization plan that stated no role for Congress. The relevant provision is found in section 716 of Public Law 119-37, which is also known as House Resolution (H. R.) 5371. Section 716 states that the USDA must do two things before expending any funds for an action that “relocates an office or employees” or “reorganizes offices, programs, or activities” (page 50 of H. R. 5371). These two things are the Agriculture Secretary “notifies in writing and receives approval from the Committees on Appropriations of both Houses of Congress at least 30 days in advance.” Public Law 119-36 is the law that Congress passed to end shutdown of October 1 to November 12, 2025. The Congressional Research Services states that this law contains the full-year budget for the USDA. This budget is for fiscal year 2026, which goes from October 2025 through September 2026.

[44] Interpreting the law: page 14 of American First Policy Institute’s policy pillar #10 on the web page titled, “Fight government corruption by draining the swamp.”

[45] Reorganization Plan No. 2 of 1953 applies to the Department of Agriculture, and it appears in 67 Stat. page 633. This 1953 report also appears as the note to 7 U. S. Code 2201. The 1953 report was submitted according to Public Law 83-109, the Reorganization Act of 1949, which is found in 63 Stat. page 203.

[46] “Farm program” refer to financial assistance to individual farms (grants or loans), not agricultural research: Congressional Research Service, December 7, 2020, U. S. Farm Programs: Eligibility and Payment Limits. The same definition is used by the General Accounting Office on its Farm Programs web page.

[47] 2,300 local USDA offices: USDA, 2025, Get Started at Your USDA Service Center, web page.

[48] This point was made in Richard Hass’s book Bill of Obligations (2023). The American Enterprise Institute’s American Survey Center also made this point in a 2024 report.

[49] See the five-minute video that the Tennessee Farm Bureau Federation posted on YouTube on September 22, 2025. At 0:23, the narrator says that Secretary Rollins held a listening session with farmers. At 4:40, Rollins is seen taking notes on what people on the panel were telling her. At 4:24, Senator Marsha Blackburn, who attended the event, said, “It’s important to sit down and listen… to hear what their issues are and be able to address those. It’s a great way to get that information. Well obviously, it’s really important that the secretary and our state’s lawmakers continue to be engaged”

[50] A USDA web page lists hundreds of journal articles that BARC researchers write or co-author each year.

[51] See Appendix B of this blog post that describes the $460 million spent on BARC construction and renovation since 1988.

[52] The four office buildings of BARC’s George Washington Carver Center (GWCC) have space to house 1,911 employees. Currently, GWCC occupation is likely below capacity.

[53] The heavy black line is the border that maps have customarily used for BARC. Such source maps include ones available from the National Agricultural Library (undated map), the National Capital Planning Commission (2019), and the EPA (2025). Within this boundary are the George Washington Carver Center (GWCC), National Agricultural Library, and the University of Maryland’s Central Maryland Research and Education Center. The map shades additional government-owned land outside of BARC that was identified using the Prince George’s County Atlas, https://www.pgatlas.com/. Arrows indicate the direction to several large facilities near BARC related to agricultural research. An approximate number of employees at these facilities is stated in Table 1 of the September 16, 2025, post about BARC on the Greenbelt Online blog. Just outside BARC’s customary boundaries are the USDA APHIS Plant Pathogen Diagnostics Laboratory (BARC Building 580) and the USDA National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) Berg National Plant Materials Center (BARC Building 509). While the 1996 Greenbelt National Historical Landmark nomination form does not include a map (PDF file and referring web page), a map is included on page 73 of the 1994 PG County study and page 22 of the Maryland Historic Trust’s copy of the 1980 nomination of BARC as a historic district (PDF file and referring web page).

[54] On November 12, 2025, Congress passed Public Law 119-37. Page 19 states $3 million of funding for BARC “construction and facilities improvement.”

Leave a Reply